INTRODUCTION

Molecular hydrogen (i.e. H2 gas) is gaining significant attention from academic researchers, medical doctors, and physicians around the world for its recently reported therapeutic potential [1]. One of the earliest publications on hydrogen as a medical gas was in 1975, by Dole and colleagues from Baylor University and Texas A&M [2]. They reported in the journal Science that hyperbaric (8 atm) hydrogen therapy was effective at reducing melanoma tumors in mice. However, the interest in hydrogen therapy only recently began after 2007, when it was demonstrated that administration of hydrogen gas via inhalation (at levels below the flammability limit of 4.6%) or ingestion of an aqueous solution containing dissolved hydrogen, could also exert therapeutic biological effects [3]. These findings suggest hydrogen has immediate medical and clinical applications [4].

This MHI article does not discuss negative hydrogen ions, (hydride, H-), pH (e.g. alkaline water), microclustered water, or other topics that are subject to pseudoscientific claims.

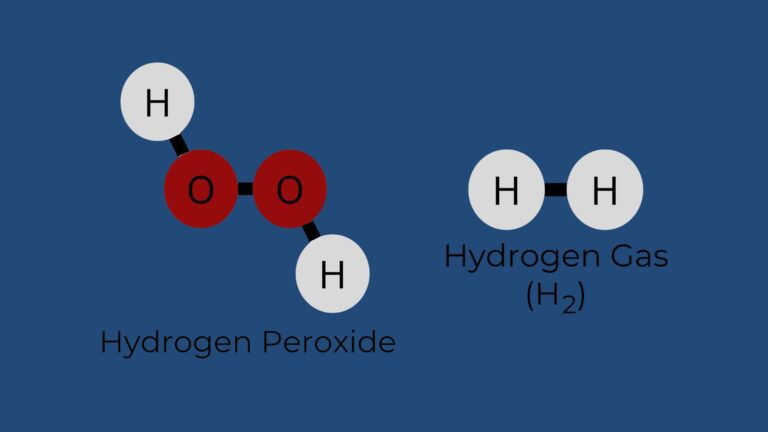

In 2007, Dr. Ohta’s team reported in Nature Medicine [3] that inhalation of 2-4% hydrogen gas significantly reduced the cerebral infarct volumes in a rat model of ischemia-reperfusion injury induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Hydrogen was more effective than edaravone, an approved clinical drug for cerebral infarction, but with no toxic effects (See figure below). The authors further demonstrated that dissolved hydrogen in the media of cultured cells, at biologically relevant concentrations, reduces the level of toxic hydroxyl radicals (•OH), but does not react with other physiologically important reactive oxygen species (e.g. superoxide, nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide).

This biomedical research on hydrogen is still in its infancy with only around 2000 articles and 1,600 researchers, but these publications and researchers suggest that hydrogen has therapeutic potential in over 170 different human and animal disease models and in essentially every organ of the human body [5]. Hydrogen appears to provide these benefits via modulating signal transduction, protein phosphorylation, and gene expressions (See section Pharmacodynamics) [4].

The idea of therapeutic gaseous molecules is not a new concept. For example, carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and of course nitric oxide (NO•), which was initially ridiculed by skeptics, but later was subject to a Nobel Prize, are all biologically active gases [6]. However, it may still be difficult to believe that H2 can exert any biological effect because, in contrast to these other gases, hydrogen is a non-radical, non-reactive, non-polar, highly diffusible neutral gas, thus it is unlikely to have specific binding sites or interact with specificity on a specific receptor [7].

From an evolutionary perspective, it may not be strange that hydrogen exerts a biological effect [8]. In addition to its role in the origins of the universe, hydrogen was also involved in the genesis of life and played an active role in the evolution of eukaryotes [9]. Over the millions of years of evolution, plants and animals have developed a mutualistic relationship with hydrogen-producing bacteria resulting in basal levels of molecular hydrogen in eukaryotic systems. This constant exposure to molecular hydrogen may have conserved the original targets of hydrogen, as can be extrapolated by genetic remnants of hydrogenase enzymes in higher eukaryotes. Alternatively, but not exclusively, eukaryotes may have developed sensitivity to molecular hydrogen over the millions of years of evolution [7, 10].

METHODS OF ADMINISTRATION

Molecular hydrogen can be administered via inhalation [11], ingestion of solubilized (dissolved) hydrogen-rich solutions (e.g. water, flavored beverages, etc.) [12], hydrogen-rich hemodialysis solution [13], intravenous injection of hydrogen-rich saline [14], topical administration of hydrogen-rich media (e.g., bath, shower, and creams) [15], hyperbaric treatment [2], ingestion of hydrogen-producing material upon reaction with gastric acid [15], ingestion of non-digestible carbohydrates as prebiotic to hydrogen-producing intestinal bacteria [16], rectal insufflation [17], and other methods. [15].

Read How to Administer Molecular Hydrogen? Best Practices

PHARMACOKINETICS

Hydrogen’s unique physicochemical properties of hydrophobicity, neutrality, size, mass, etc. afford it with superior distribution properties allowing it to rapidly penetrate biomembranes (e.g., cell membranes, blood-brain, placental, and testis barrier) and reach subcellular compartments (e.g., mitochondria, nucleus, etc.) where it can exert its therapeutic effects [15]. Although various medical clinics in Japan use intravenous injection of hydrogen-rich saline, the most common methods are inhalation and drinking hydrogen-rich water. The pharmacokinetics of each method are still under investigation but are dependent on dosage, route, and timing. An article published in Nature’s Scientific Reports [18] compared inhalation, injection, and drinking with different hydrogen concentrations and found helpful insights for clinical use. Based on this and various studies, we briefly summarize the pharmacokinetics of inhalation and drinking.

INHALATION OF HYDROGEN

For inhalation, a 2-4% hydrogen gas mixture is common because it is below the flammability level; however, some studies use 66.7% H2 and 33.3% O2, which is non-toxic and effective, but flammable. Inhalation of hydrogen reaches a peak plasma level (i.e., equilibrium based on Henry’s Law) in about 30 min, and upon cessation of inhalation, the return to baseline occurs in about 60 min.

DRINKING DISSOLVED HYDROGEN

The concentration/solubility of hydrogen in water at standard ambient temperature and pressure (SATP) is 0.8 mM or 1.6 ppm (1.6 mg/L). For reference, conventional water (e.g. tap, filtered, bottled, etc.) contains less than 0.0000002 mg/L of H2, which is well below the therapeutic level (See Q&A 7-8). The concentration of 1.6 mg/L is easily achieved by many methods, such as simply bubbling hydrogen gas into water. Because of molecular hydrogen’s low molar mass (i.e., 2.02 g/mol H2 vs. 176.12 g/mol vitamin C), there are more hydrogen molecules in a 1.6-mg dose of H2 than there are vitamin C molecules in a 100-mg dose of pure vitamin C (i.e., 1.6 mg H2 has 0.8 millimoles of H2 vs. 100 mg vitamin C has 0.57 millimoles of vitamin C).

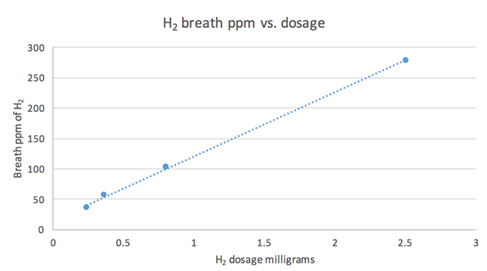

The half-life of hydrogen-rich water is shorter than other gaseous drinks (e.g., carbonated or oxygenated water), but therapeutic levels can remain for a sufficiently long enough time for easy consumption. Ingestion of hydrogen-rich water results in a peak rise in plasma and breath concentration in 5-15 min in a dose-dependent manner (see figure). The rise in breath hydrogen is an indication that hydrogen diffuses through the submucosa and enters systemic circulation where it is expelled out the lungs. This increase in blood and breath concentration returns to baseline in 45-90 min depending on the ingested dosage.

PHARMACODYNAMICS

Although a significant amount of research in cells, tissues, animals, humans, and even plants has confirmed hydrogen’s effect in biological systems, the exact underlying molecular mechanisms and primary targets remain elusive [19].

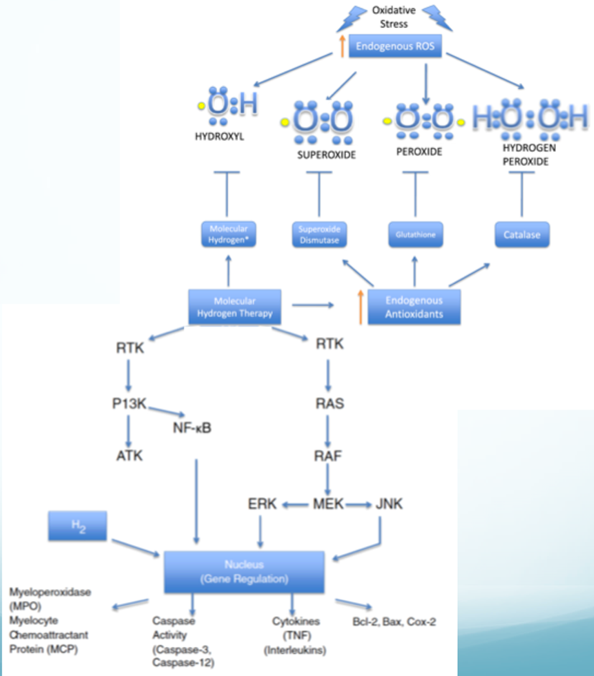

ANTIOXIDANT-LIKE EFFECT

It was initially suggested that the beneficial effect of hydrogen was due to an antioxidant as hydrogen selectively neutralized cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals [3] in vitro. However, although H2 reduces •OH radicals [20], as has been shown in various systems [3, 21, 22], it may not occur via direct scavenging, and it also

cannot fully explain all the benefits of hydrogen [23]. For example, in a double-blinded placebo-controlled trial in rheumatoid arthritis [24], hydrogen had a residual effect that continued improving the disease symptoms for four weeks after hydrogen administration was terminated [24]. Many cell studies also show that pre-treatment with hydrogen has marked beneficial effects even when the assault (e.g., toxin, radiation, injury, etc.) is administered long after all the hydrogen has dissipated out of the system [25-27]. Additionally, the rate constants of hydrogen against the hydroxyl radical are relatively slow (4.2 x 107 M-1 sec-1) [20], and the concentration of hydrogen at the cellular level is also quite low (micromolar levels), thus making it unlikely that H2 could effectively compete with the numerous other nucleophilic targets of the cell [28]. Lastly, if the mechanism were primarily associated with scavenging of hydroxyl radicals, then we should see a greater effect from inhalation compared to drinking, but this is not always the case [29, 30]. In short, we consider it inaccurate or at least incomplete to claim that the benefits of hydrogen are due to its acting directly as a radical-scavenging antioxidant. Indeed, hydrogen is selective because it is a very weak antioxidant and thus does not neutralize important ROS or disturb important biological signaling molecules. Nevertheless, a metabolic tracer study [31] using deuterium gas demonstrated that, under physiological conditions, deuterium gas is oxidized, and the oxidation rate of hydrogen increases with an increasing amount of oxidative stress [32], but the physicochemical mechanism for this may still not be direct radical scavenging [31]. However, not all studies show that hydrogen is oxidized via mammalian tissues [33], and it has also been reported that deuterium gas did not exert a therapeutic effect in the model studied whereas 1H did (unpublished data).

NRF2 PATHWAY

Unlike conventional antioxidants [34], hydrogen does have the ability to reduce excessive oxidative stress [23], but only under conditions where the cell is experiencing abnormally high levels of oxidative stress that would be harmful and not hormetic.

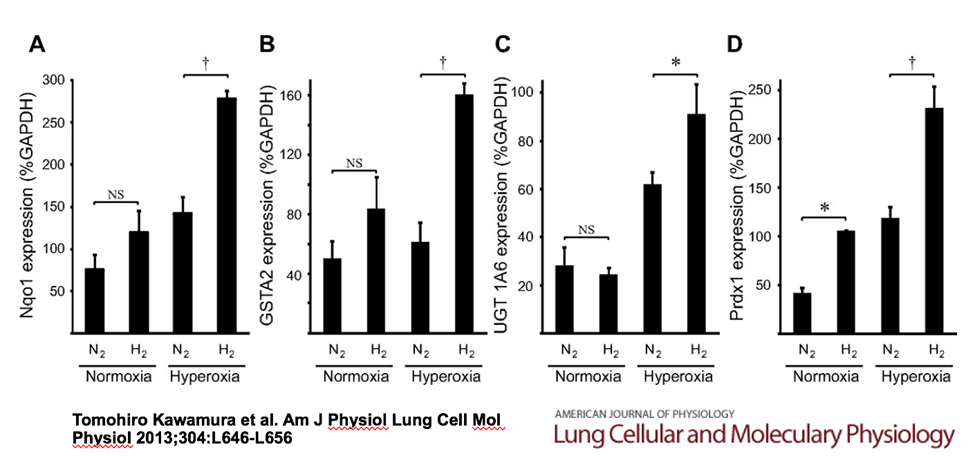

One mechanism that hydrogen uses to protect against oxidative damage is by the activation of the Nrf2-Keap1 system and subsequent induction of the antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway, which leads to the production of various cytoprotective proteins like glutathione, catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, heme-1 oxygenase, etc. [5, 35, 36]. In some disease models, the benefits of hydrogen are negated by using Nrf2 gene knockouts [37, 38], Nrf2 genetic silencing using iRNA [39], or pharmacologically blocking the Nrf2 pathway [40, 41]. Importantly, hydrogen only activates the Nrf2 pathway when there is an assault (e.g. toxin, injury, etc.) [40] as opposed to constituently acting as a promoter, which could be harmful [42, 43]. The method that hydrogen activates the Nrf2 pathway remains unclear [5].

SIGNAL MODULATION

Besides the potential scavenging of hydroxyl radicals and/or activation of the Nrf2 pathway, hydrogen may ameliorate oxidative stress via a signal-modulating effect [5] and reduce the formation of free radicals [44], such as downregulating the NADPH oxidase system [45]. The various signal-modulating effects of hydrogen are responsible for mediating the anti-inflammatory, anti-allergy, and anti-obesity effects of hydrogen. Hydrogen has been shown to downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, etc.) [46], attenuate the activation of TNF-α [24], NF-κB [47], NFAT [30, 48], NLRP3 [49, 50], HMGB1 [51], and other inflammatory mediators [5]. Additionally, hydrogen has beneficial effects on obesity and metabolism by increasing the expression of FGF21 [52], PGC-1α [53], PPARα [53], and more. [54]. Additional 2nd messenger molecules or transcription factors affected by hydrogen include ghrelin [55], JNK-1 [45], ERK1/2 [56], PKC [57], GSK [58], TXNIP [49], STAT3 [59], ASK1 [60], MEK [61], SIRT1 [62], and many more. Over 200 biomolecules are altered by hydrogen administration including over 1000 gene expressions.

However, the primary targets and master regulators responsible for these changes are still elusive [46]. There are many feedback systems and loops to consider, which makes it difficult to determine if we are detecting the cause or the effect of hydrogen administration.

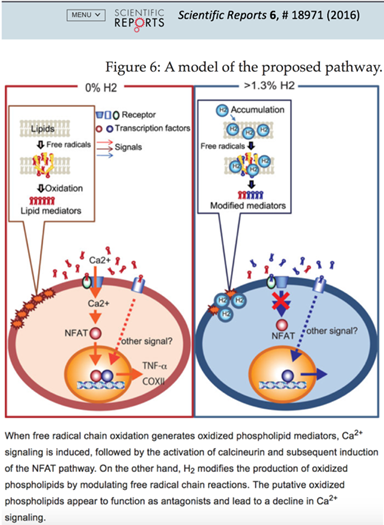

The exact mechanism of how hydrogen modulates signal transduction, gene expression, and protein phosphorylation is still being investigated [5]. A recent publication [63] in Scientific Reports provides good evidence to suggest that one of the mechanisms through which hydrogen accomplishes the various signal-modulating effects is by modifying lipid peroxidation in the cell membrane. In cultured cells, at biologically relevant concentrations, hydrogen suppressed the free radical chain reaction-dependent peroxidation and recovered Ca2+-induced gene expressions, as determined by comprehensive microarray analysis (see Figure 6) [63].

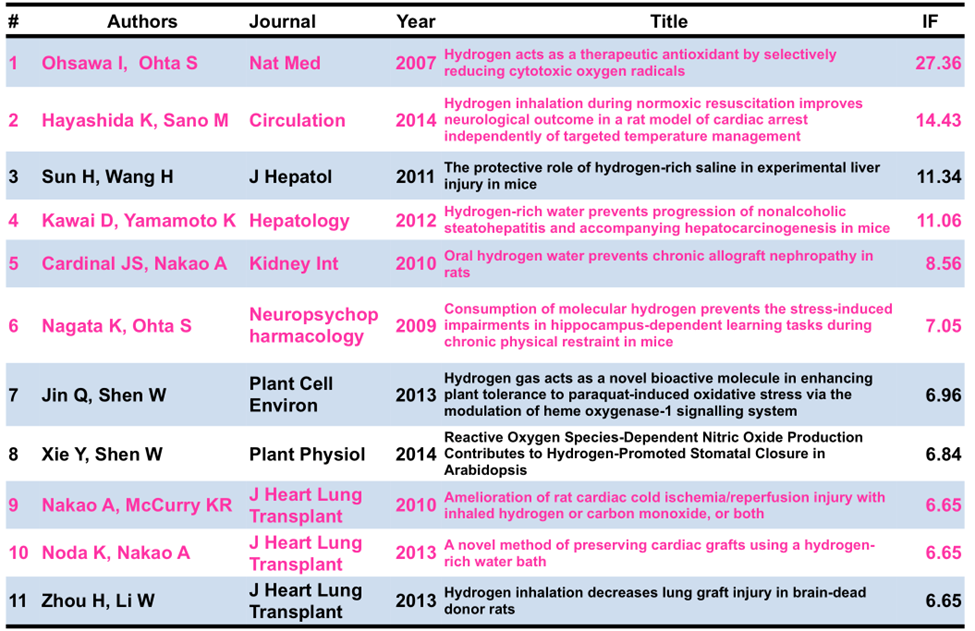

SCIENTIFIC RECOGNITION OF HYDROGEN

Although the primary targets or exact biochemical mechanisms of hydrogen are still not fully understood, the therapeutic effect in cells, tissues, animals, humans and even plants [64] is becoming widely accepted due to the now over 2000 peer-reviewed articles and the 1,600 researchers on the medical effects of hydrogen. The quality of the publications is also improving with an average impact factor (IF) of the journals publishing hydrogen is about 3. The table below shows a few of the studies published in the higher IF journals, which range from six to 27.

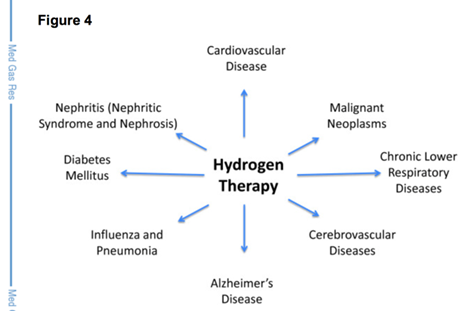

HYDROGEN AND IMMEDIATE MEDICAL APPLICATIONS

Hydrogen as a medical gas is also growing because it has immediate medical applications to help with many of the current health crises [65, 66]. Dixon and colleagues of Loma-Linda University reported that hydrogen has potential to help with the top 8/10 disease-causing fatalities as listed by the Centers of Disease Control [67]. Dr. Banks, from the VA/U of Washington, reported that ingestion of hydrogen-rich water was protective against neurodegenerative changes induced by traumatic brain injury in mice [68]. Their results show that hydrogen administration reduced brain edema, blocked pathological tau expression, and maintained ATP levels. This and other studies have profound effects for events where brain injury (e.g. concussion, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, etc.) is a common occurrence [69]. Although many people report dramatic effects of hydrogen therapy, from rapid pain and inflammation relief to normalization of glucose and cholesterol levels, other people may not notice any immediate or observable benefits. Hydrogen is not considered a powerful drug, and as mentioned only helps bring the cell/organ back to homeostasis without causing major perturbations. Perhaps some of the reported dramatic effects can be attributed to the placebo effect or other things, although some researchers have noted that some people are more sensitive to hydrogen and experience greater effects. More human studies are needed to answer these questions.

HUMAN RESEARCH

Although the research on hydrogen looks promising in the cell or animal models, more long-term clinical trials are required to confirm its efficacy in humans [70]. There are only a total of 140 human studies, and most of them lack a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized design with an adequate number of subjects. A few of these clinical studies suggest that ingestion of hydrogen-rich water was beneficial for metabolic syndrome [71], diabetes [72], and hyperlipidemia [73, 74]. Another 1-year placebo-control clinical study suggested that hydrogen-rich water is beneficial for Parkinson’s disease [75], while other clinical studies suggest significant benefits for rheumatoid arthritis [24, 76], mitochondrial dysfunction [77], exercise performance [78], athletic recovery time [79], wound healing [80-82], reductions of oxidative stress from chronic hepatitis B [83], improvements to blood flow [84], and periodontitis [85], in dialysis [86, 87], and also the quality of life in patients receiving radiotherapy for tumors [88] and others [5].

As of 2015, there have been an additional 15+ human studies completed with promising results, which are in the process of manuscript preparation and publication through the peer-reviewed process. In 2023, there are now three systematic reviews with meta-analyses on the effects of molecular hydrogen. These are in cancer [98], exercise-induced fatigue [99], and blood lipids [100], all of which suggest hydrogen has favorable effects. However, more human studies are required to determine the proper dosage, timing, method of administration, and for which diseases, and potentially genotypes, hydrogen is most effective [7]. Hydrogen is still in its infancy, and more data is required before we can scientifically claim any real benefit, but the preliminary data is intriguing. The research on disease models, mechanisms of action, and clinical studies are particularly relevant because the high safety profile of molecular hydrogen makes it a superior choice [89].

SAFETY

Hydrogen is naturally produced by intestinal flora upon digestion of fibers [90]. A study from the University of Florida and the Forsythe Institute of Boston, Massachusetts confirmed that hydrogen produced from bacteria exerted therapeutic effects [91]. They found that reconstitution of intestinal microbiota with H2-producing E. coli, but not H2-deficient mutant E. coli, was protective against Concanvalin A-induced hepatitis. Other studies also show that bacterially produced hydrogen from acarbose administration is therapeutic [92]. Perhaps this helps explain why a large clinical trial from the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) found significant reductions in cardiovascular events by those taking the hydrogen-producing acarbose drug [92, 93]. These studies not only suggest the therapeutic action of molecular hydrogen, but also demonstrate its high safety profile. Hydrogen is very natural to our bodies, as we are exposed to it on a daily basis as a result of normal bacterial metabolism [1]. Additionally, hydrogen gas has also been used in deep sea diving since the 1940s to prevent decompression sickness [94, 95]. Hundreds of human studies for deep sea diving have shown inhalation of hydrogen gas, at orders of magnitude greater than what is needed for therapeutic use, is well-tolerated by the body with no chronic toxic effects [96]. In some people, however, it is reported that hydrogen may result in loose stools [97], and in rare cases with diabetics, hypoglycemia [77], which is controlled by reducing the level of insulin administered. The hundreds of studies on hydrogen from bacterial production, deep sea diving, and recent medical applications have not revealed any direct noxious side effects of hydrogen administration at biologically therapeutic levels. Such a high safety profile may be considered paradoxical because chemotherapeutic agents that exert biological effects should have both beneficial and noxious effects depending on dosage, timing, location, duration, etc. However, such noxious effects have yet to be reported for hydrogen. However, perhaps the noxious effects are so transient and mild that they are masked by the beneficial effects, or are even what mediate the beneficial effects via hormetic pathways. [98]

Read Is Molecular Hydrogen Safe?

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The goal of the Molecular Hydrogen Institute (MHI) is to provide education on, advance research about, and promote awareness of molecular hydrogen’s therapeutic potential. It is uncommon to find a treatment that has both a high therapeutic potential and a high safety profile; hydrogen appears to fit this combination [23]. Some researchers have become interested in hydrogen due simply to its unforeseen ability to have a biological effect; with the realization that hydrogen is both safe and effective, a moral obligation develops to advance the research, education, and awareness of hydrogen as a medical gas. We welcome other biomedical researchers to join us in elucidating the in vitro molecular mechanisms of hydrogen, and to perform well-controlled clinical trials on hydrogen in order to understand the best dosage, timing, genotype, and method of hydrogen administration. With only a few hundred peer-reviewed articles and a couple thousand biomedical researchers, hydrogen research is still in its infancy. However, the preliminary studies suggest that molecular hydrogen is something that should be pursued, investigated, and elucidated for the potential benefit of disease prevention and treatment.